Justin’s Testimony

Justin’s Testimony

In his magnum opus, Dialogue with Trypho,[1] Justin Martyr taught that there were moments in history when God personally visited different people. But it wasn’t the Father, the Holy Spirit, or God in general who made these special appearances. It was the Son. Since he was striving to bring a Jewish man to saving faith in Messiah Jesus, Justin looked to prove his case from the Hebrew Bible:

“I shall give you another testimony, my friends,” said I, “from the Scriptures, that God begat before all creatures a Beginning, [who was] a certain rational power [proceeding] from Himself, who is called by the Holy Spirit, now the Glory of the Lord, now the Son, again Wisdom, again an Angel, then God, and then Lord and Logos; and on another occasion He calls Himself Captain, when He appeared in human form to Joshua the son of Nave (Nun).[2]

And with those words, the great second-century church father summarized a truth that is so profound and deep in meaning, that even in eternity the saints may not fully comprehend it. The Son of God didn’t wait for thousands of years to become incarnate before He visited and interacted with man. As God, Jesus personally communicated with His creation on a regular basis, from Adam and Eve onward.

Many Christians find it difficult to read and study the Old Testament. They prefer to remain in the New, in large part because Jesus is there. Once the saint sees Jesus throughout the entire Bible—not just spiritually, but actually in person—it becomes a more exciting and rewarding experience to become immersed in all of God’s Word. It is, then, of tremendous spiritual value to consider the various ways in which Jesus has appeared before He became a man.

Christophanies

Appearances of the preincarnate Christ may be understood as Old Testament Christophanies. A Christophany (or Messiahophany if you prefer) is a non-incarnate appearance or manifestation of Christ, the Son of God, to one or more people. The traditional definition of Christophany limited its application to New Testament manifestations of Christ after the Resurrection. Since the late twentieth century, the term has been applied more and more to manifestations in the Old Testament as well.

Christ’s appearance near Damascus is a classic example of a Christophany from the New Testament. As Saul was approaching Damascus, a light from heaven suddenly shone around him. A voice asked Saul why he was persecuting Him. Saul asked who it was that was speaking, and the voice answered, “I am Jesus whom you are persecuting” (Acts 9:3–5; 22:6–8; 26:13–15). Another New Testament example is the Patmos Christophany. On the isle of Patmos, the Apostle John beheld one like the son of man. He was clothed in a long robe with a gold sash across His chest. His hair was like wool, white as snow, and His eyes were like flames of fire. His feet were like polished bronze, refined in a furnace, and His voice roared like many waters. He held seven stars in His right hand, and a sharp two-edged sword came out of His mouth. His face was shining like the sun in all its brilliance. This individual said that He was the first and the last and the living One. He was dead but is now alive forevermore; He holds the keys of death and of Hades (Rev 1:12–18). This was undoubtedly a visitation by the glorified Jesus Christ, for He is soon after identified as the Son of God (Rev 2:18).

While Christophanies in the New Testament are easier to identify, they are small in number when compared to those in the Old Testament. A Christophany is a more specific form of a theophany, an appearance of God to one or more people. Through some investigation, it becomes evident that many of the theophanies in the Old Testament are likely Christophanies. There is even a case to be made that the vast majority of theophanies are Christophanies. For it is the role of the Son to explain the Father, revealing Him to mankind (John 1:18). Each time God took on a human form to communicate with man it foreshadowed the Incarnation, when the Son of God actually became a man in order to dwell among us (Matt 1:23; John 1:14).

A brief explanation of each Old Testament name for Jesus from Justin’s list will give the background needed to appreciate the many examples of Christophanies that are to come in future articles.

The Word of Yahweh

The Targumim

The targumim (singular: targum) were spoken paraphrases of Hebrew Scripture in the common language—which was often Aramaic—with some dating from at least the time of Ezra (ca. 458 BC). They were necessitated by the Babylonian Captivity, which had stripped the average Jewish person’s ability to read and speak Hebrew. Texts found in the Dead Sea Scrolls—notably the Job Targum from Qumran cave XI—indicate that some targumim were written down in Aramaic before the first century AD. Out of the several that would come to be recorded, two of them—Targum Onkelos on the Torah and Targum Jonathan ben Uzziel on the Nevi’im (Prophets)—were granted official status in the Babylonian Talmud.[3] They were regularly read aloud in the Synagogues of the Talmudic period. And they continue to be used in the liturgy of Yemenite synagogues to this day. Another prominent targum is Pseudo-Jonathan—a western targum on the Torah, which used to be mistakenly attributed to Jonathan ben Uzziel. The targumim are often not so much word-for-word translations, as much as they are midrashic expansions that were intended to teach the audience truths or nuances that would have been otherwise missed by the layman. They provide us with great insight into how audiences closer to the original—both in time and culture—understood the Hebrew Scriptures. The targumim passages on the Word of the Lord are especially helpful in the study of Old Testament Christophanies.

Rational Power

The certain rational power that proceeds from God is the Word of Yahweh. Though there are many verses that Justin Martyr could have been referring to, there is one in particular that was likely in mind:

So will My word be which goes forth from My mouth;

It will not return to Me empty,

Without accomplishing what I desire,

And without succeeding in the matter for which I sent it. (Isa 55:11 NASB 95)

Now consider the Targum Jonathan version, which is more in line with Justin’s phrasing:

Thus shall be the word of my kindness, which proceeds from my presence,

it is not possible that it shall return to my presence void,

but it shall accomplish that which I please,

and shall prosper in the thing whereto I sent it.

While both versions teach the same thing, the targum brings some clarity in having the word come from God’s presence rather than from His mouth. The word is more than just something said; it is depicted much like an agent who is sent forth on a mission, one he is certain to complete. This isn’t to suggest that Isaiah 55:11 describes a Christophany. But the verse does provide us with a general principle that can be applied to how the personified Word behaves and the intimate relationship He has with God.

John opened his Gospel by identifying who Jesus was, not only before His incarnation, but even before the universe was created through Him:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through Him, and apart from Him nothing came into being that has come into being. (John 1:1–3)

Out of the many ways the apostle could have described the preincarnate Jesus, he opted to identify Him as the “Logos”—translated as “Word” in English. The Word is an indispensable part of God’s complex unity; He is simultaneously with God while also being God. When nothing else existed except for God, the Word was there. While it was God who created the universe (Gen 1:1), only through the Word was anything created (cf. Gen 1:3 and other uses of “God said” in the chapter; Ps 33:6; Col 1:16; Heb 1:2). The Word miraculously took on flesh and tabernacled among us as Jesus Christ (John 1:14). As the Son of God, Jesus went forth to accomplish His Father’s will, in much the same way that the Word proceeds from God’s presence.

John also opened his first epistle with a discussion of the eternal Son becoming incarnate, referring to Him as “the Word of Life” (1 John 1:1–2). And in John’s Apocalypse, Jesus is once again identified as the Word:

He is clothed with a robe dipped in blood, and His name is called The Word of God. (Rev 19:13)

The use of “the Word” to identify the Son isn’t limited to preincarnate references. Even at the Second Coming, Jesus will still be known as the Word. He held the title when He came as the Lamb Messiah and will continue to hold it as the Lion Messiah. “The Word of God” describes who Jesus was, who He is, and who He always will be (cf. Heb 13:8).

Logos and Memra

The Greek logos is typically translated as word. Based on the context, it can also indicate an utterance by a living voice, the embodiment of an idea, reason, and several other related actions and concepts. The first known use of the logos as a technical term was by the Greek philosopher Heraclitus around 500 BC. He used it to designate the divine reason which governs the universe. Greek philosophers continued to use logos along similar lines of thinking in their own systems. It was a key component in Plato’s Theory of Forms. Philo of Alexandria (ca. 25 BC–ca. 50 AD)—a Hellenistic Jewish Philosopher—made special use of the logos in his attempt to synthesize Moses, the prophets, and Plato into one philosophical system. While the Greeks didn’t couch the divine logos in anthropomorphic terms as John did, they were certainly in a position to appreciate what the apostle was teaching.

That being said, John wasn’t borrowing from Greek philosophy or Philo to make his point. The concept of the divine Word had been long taught by the Hebrews. And they did often portray the Word as a person. John’s usage of Logos was rooted in the same Jewish thought behind the targumim’s similar usage of memra.[4] The Aramaic memra is the equivalent of logos. It was added to verse after verse in the targumim to make it clear that it was specifically the Word of Yahweh who was intended, rather than Yahweh in general. In several places the addition of memra resulted in the divine Word communicating with one or more people. If the originators of the targumim were correct to do this—even if only in some passages—it means that the preincarnate Jesus, as the Word of the Lord, was visiting mankind in the Old Testament! We’ll look at one astonishing example after another in later articles. Each one is guaranteed to make you see Jesus more clearly in the Hebrew Bible.

The Angel of Yahweh

Perhaps the most enigmatic figure in the entire Old Testament is the Angel of Yahweh. He certainly is the most mysterious among the few others who appear as often as he does. On the one hand, He is spoken of as an angel, representing Yahweh. On the other hand, He is often identified as God or Yahweh Himself. It is clear that this is no ordinary angel. The Hebrew mal’ak doesn’t always indicate an angelic being as commonly imagined. It often designates a messenger, ambassador, or envoy. At times, it specifically indicates the theophanic angel—Yahweh the Messenger. Some translations, notably the Geneva Bible, even capitalize Angel in passages where the translators found that the divine Angel is being referenced.

In several places, the Angel of Yahweh is called the Angel of God (malak Elohim). Another one of His names, the Angel of His Presence, is found in Isaiah 63:9. And in Malachi 3:1, He is referred to as the Messenger (or Angel) of the Covenant.

The Hebrew malak YHWH, commonly translated as “the angel of the LORD” in English bibles, is in the grammatical form known as s’michut. S’michut, which means “closeness”, consists of two words set side by side that are meant to be understood and pronounced as just one word. Think of s’michut as the Hebrew version of a compound word. The main difference is that in English the first word in a compound describes the second; moonlight is a type of light, not a type of moon. In Hebrew, the second word in the compound describes the first. In the case of malak YHWH, the two component nouns were joined in order to form a specific name. This name could be translated as “Yahweh-Angel” just as accurately as it is translated as “the Angel of the LORD.”

Asher Intrater, a teacher and ministry leader, concluded that the Angel’s name being in the s’michut form was significant (he prefers Yehovah over Yahweh):

The paired-noun grammatical form makes the expression “Angel of the Lord” to be 1) proper, and 2) merged.

Proper—While it could be argued that Angel-Yehovah is any one of a number of angels sent from God, the grammatical form points to it being a proper noun. It is THE Angel-Yehovah, not ANY angel from Yehovah. I do not know of even one example in the entire Hebrew Bible in which the term Angel-Yehovah is in “s’michut” form, where the context demands that it is referring to a generic angel, or one of a group of angels.

Merged—The two nouns, Angel and Yehovah, modify one another. This is not a “ball” and a “game” but a “ball-game.” It is a “ball”—type of game. This is not just an angel, but a Yehovah-type angel. The two terms cannot be separated from one another. The nature of this angel is determined by the name Yehovah. Angel and Yehovah are paired noun partners.

This grammatical structure fits perfectly the description of the figure that appeared to our prophets and patriarchs. The “s’michut” is so unusual and so fitting and so perfect, that I cannot escape the impression that this grammatical form was sovereignly predestined and planned by God for the primary purpose of describing this one Person in the Hebrew Bible.

It is a unique grammatical form to define a unique individual. There is no one else like Him. A special grammatical construct was needed to be able to name Him. No man fits that category; no angel fits that category; even God our Heavenly Father does not fit that category.[5]

The words Malak YHWH are, on rare occasions, used of other messengers. However, we are always told who they are (e.g., Hag 1:13). When the Old Testament simply mentions the Angel of the Lord, it refers to a specific divine messenger.

The understanding that the Angel is the second person of the Trinity is rooted in the overall role of the Son as the revealer of the Father:

No one has seen God at any time; the only begotten God who is in the bosom of the Father, He has explained Him. (John 1:18)

It is the Greek exegesato from which we get “exegete.” Jesus exegeted or explained the Father by drawing from and revealing Him before mankind. The Son is the image of the invisible God (Col 1:15) and the exact representation of His nature (Heb 1:3). This is why Jesus was able to teach that no one had ever seen the Father (John 6:46), while also stating, “He who has seen Me has seen the Father” (John 14:9). There are several instances where people saw God either in visions or as a theophany (e.g., Gen 18; Exod 33:21–23; Isa 6:1–5). But never was God seen in His fully unveiled glory (Deut 4:12; Ps 97:2; 1 Tim 1:17; 6:16; 1 John 4:12). And if it theoretically did happen, that person couldn’t have continued to live (Exod 33:20). Some of the individuals who had encountered the Angel were terrified that their deaths were imminent (e.g., Judg 6:22–23; 13:22). However, no sudden death ever came, even though they had seen God. As a Christophany, the Angel revealed Yahweh before men without exposing them to God’s unbridled essence, just as Jesus did after the incarnation.

While the Angel appeared regularly throughout the Old Testament, He never appeared again after the incarnation. Jesus actually became a human, which appearances of the Angel were likely pointing to. Out of the persons of the Trinity, the Angel could only be the Son. The Angel was with God, and the Angel was God—just as we see with the Word in John 1:1.

Indeed, the Angel of Yahweh is almost an interchangeable name for the Word of Yahweh. One could be switched with the other without doing much damage to the meaning of the passages in which they appear. Because the Angel is said to be both with God and God Himself, those with theological positions that are incompatible with such a concept have gone to great lengths to explain away the obvious. This even includes replacing Him with a fictional being that is highly exalted but still less than God—Metatron—the archangel of rabbinical Judaism.

The Angel of the Lord stopped Abraham from sacrificing Isaac, He appeared to Moses in the burning bush, He stood in the way of Balaam and his talking donkey, He ascended toward heaven, He sent four horsemen forth to patrol the earth, and He symbolized Himself taking on the sins of Joshua the high priest. The Angel performed even more marvelous works that connect Him with the person we know as Jesus in the New Testament.

The Angel of the Lord stopped Abraham from sacrificing Isaac, He appeared to Moses in the burning bush, He stood in the way of Balaam and his talking donkey, He ascended toward heaven, He sent four horsemen forth to patrol the earth, and He symbolized Himself taking on the sins of Joshua the high priest. The Angel performed even more marvelous works that connect Him with the person we know as Jesus in the New Testament.

The Glory of Yahweh

The Shekinah

The Hebrew term Shekinah originally comes from rabbinic literature; it denotes the observable, nesting presence of Yahweh. While the actual word doesn’t appear in the Bible, matching descriptions and other names for it—principally, the “glory of Yahweh”—surely do. The Messianic-Jewish scholar, Arnold Fruchtenbaum, provides us with both a definition of the Shekinah (he transliterates it as Shechinah), and background information that connects it to Jesus:

The Hebrew form is Kvod Adonai, which means “the glory of Jehovah” and describes what the Shechinah Glory is. The Greek title, Doxa Kurion, is translated as “the glory of the Lord.” Doxa means “brightness,” “brilliance,” or “splendor,” and it depicts how the Shechinah Glory appears.

Other titles give it the sense of “dwelling,” which portrays what the Shechinah Glory does. The Hebrew word Shechinah, from the root shachan, means “to dwell.” The Greek word skeinei, which is similar in sound as the Hebrew Shechinah (Greek has no “sh” sound), means “to tabernacle.”

As has been stated, the Shechinah Glory is the visible manifestation of the presence of God. In the Old Testament, most of these visible manifestations took the form of light, fire, or cloud, or a combination of these. A new form appears in the New Testament: the Incarnate Word.

At times the Shechinah Glory is closely associated with one or more of four elements: first, the Angel of Jehovah; second, the Holy Spirit; third, the cherubim; and fourth, the motif of thick darkness.[6]

The Glory of Jesus

It is the very verse which records the incarnation of the Word that also connects Him with the Shekinah:

And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us, and we saw His glory, glory as of the only begotten from the Father, full of grace and truth. (John 1:14)

By taking on flesh, the divine Word set up a tabernacle in order to dwell among men—an act in harmony with the Shekinah’s meaning and past behavior. The “glory” that John and the other disciples witnessed likely referrers to the panoply of divine attributes that Jesus exhibited and the miracles He performed as a whole. But within that greater scope is the actual manifestation of the Shekinah by Jesus at His transfiguration:

“Truly I say to you, there are some of those who are standing here who will not taste death until they see the Son of Man coming in His kingdom.” Six days later Jesus took with Him Peter and James and John his brother, and led them up on a high mountain by themselves. And He was transfigured before them; and His face shone like the sun, and His garments became as white as light. And behold, Moses and Elijah appeared to them, talking with Him. Peter said to Jesus, “Lord, it is good for us to be here; if You wish, I will make three tabernacles here, one for You, and one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” While he was still speaking, a bright cloud overshadowed them, and behold, a voice out of the cloud said, “This is My beloved Son, with whom I am well-pleased; listen to Him!” (Matt 16:28–17:5)

Since the Jewish leaders had committed the unpardonable sin of attributing the work of the Holy Spirit to Satan (Matt 12:24, 32), the return of the kingdom to Israel was no longer available at that time (Matt 13:10–11; cf. Acts 1:6–7). The Lord, then, decided to reward some of those who did follow Him with a preview of the kingdom by unveiling of the glory of Yahweh. The disciples would have readily understood why the appearance of the Shekinah meant that the Messiah had come in His kingdom. The rule of God among His people is the most basic definition of the kingdom. And it is was the presence of the Shekinah that let God’s people know that He was with them. It descended near the beginning of Israel’s kingdom of priests (Exod 19:6, 16–20) and departed at its temporary end (Ezek 10:18–19; 11:22–23). By allowing Peter, James, and John to be eyewitnesses of His majesty, Jesus kept His promise that some of them would not die until they saw the Son of Man coming in His Kingdom (16:28; cf. 2 Pet 1:16–18).

Another passage that connects the Word with the glory of the Lord is Hebrews 1:2–3:

in these last days has spoken to us in His Son, whom He appointed heir of all things, through whom also He made the world. And He is the radiance of His glory and the exact representation of His nature, and upholds all things by the word of His power. When He had made purification of sins, He sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high,

Again, it was by the Son—as the Word—that the entire universe was created (John 1:3; Col 1:16). And not only that, it is by the word of His power that it is carried forward. The Greek apaugasma, translated here as “radiance,” refers to a reflected brightness or a light shining forth from a luminous body. While Jesus reflected God’s glory in every aspect of His life and ministry, it was on full display at the transfiguration (Matt 17:1–2). It is no coincidence that the Son is mentioned as a creative agent along with Him as the radiance of God’s glory in the opening statement to the epistle (1:1–4)—an opening statement intended to introduce the fact that Jesus is superior to all previous mediators of revelation (chs. 1–2). You could say that the glorified Son is God’s final Word.

In the New Jerusalem, Jesus will shine forth the unrestrained Shekinah:

And the city has no need of the sun or of the moon to shine on it, for the glory of God has illumined it, and its lamp is the Lamb. The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it. In the daytime (for there will be no night there) its gates will never be closed; (Rev 21:22–24)

God’s glory will so fully illuminate the eternal home of the saints that the sun and moon will no longer be needed. As the Lamb, Jesus will never cease to emanate the Shekinah, proving that God is dwelling among man forever (Rev 21:3). The connection Jesus has with the Shekinah—as God’s visible and nesting presence among men—is remarkable.

Since the glory of the Lord took the form of the incarnate Word in the New Testament, it is reasonable to assume that it was radiating from the preincarnate Word in the Old Testament. While not all manifestations of the glory of the Lord indicate that the Son was present, some likely do, while others most certainly do. This includes associations with known Christophanies, such as the Angel of the Lord. Whether before or after His incarnation, the Son of God is, and always will be, a Shekinah lamp.

Wisdom Personified

Justin explained why he listed “Wisdom” as one of the names for the Son: “The Word of Wisdom, who is Himself this God begotten of the Father of all things, and Word, and Wisdom, and Power, and the Glory of the Begetter, will bear evidence to me, when He speaks by Solomon the following:”[7] The father continued by quoting Proverbs 8:22–36 in its entirety.[8] This is a passage which presents wisdom as a person. Many consider this figure to be a literary device, the same first employed by the king in Proverbs 1:20. Justin supposed that this particular use was representative of the true personification of wisdom—the divine Word and the glory of the Lord.

Speaking in first person, wisdom declared that he was possessed by Yahweh from the beginning. He was established from time everlasting, before the depths, mountains, or first speck of dust was created (vv. 22–26). When God established the universe, wisdom was there—not as an idle spectator, but as a master architect at His side (vv. 27–30). Wisdom was God’s daily delight, rejoicing always in His presence. He further rejoiced in God’s inhabited world and was delighted with humanity (vv. 30–31).

Wisdom moved from describing himself and his deeds to exhorting his children:

“Now therefore, O sons, listen to me,

For blessed are they who keep my ways.

“Heed instruction and be wise,

And do not neglect it.

“Blessed is the man who listens to me,

Watching daily at my gates,

Waiting at my doorposts.

“For he who finds me finds life

And obtains favor from the Lord.

“But he who sins against me injures himself;

All those who hate me love death.” (vv. 32–36)

It is easy to see why Justin read this and thought of Jesus. As the Word, Jesus was in the beginning with God and everything was made through Him (John 1:1–3; Col 1:16–17; Heb 1:2). The triune God found that creation, including mankind, was very good (Gen 1:26, 31). The Son had glory with the Father before the world was (John 17:5). The Messiah is God’s chosen one, in whom His soul delights (Isa 42:1). Jesus loved the sons of man so much—that in order to provide for them instruction and salvation—He became one. Jesus said that if you love Him, you will keep His commandments (John 14:15). He is the resurrection and the life (John 11:25–26; cf. 14:6). Knowing God and the Messiah He has sent not only leads to life, it is the very definition of life (John 17:3). Truly, whoever comes to know Jesus finds life (e.g., John 3:16; 11:25–26; 14:6) and God’s favor (e.g., Rom. 4:5). He who doesn’t obey the Son won’t see life, and the wrath of God abides on him (John 3:36).

In addition to the passages on the Messiah that are reminiscent of this one from Proverbs, there are other points of connection. Jesus employed a similar personification of wisdom, applying it to His life and deeds (Matt 11:19). He may have even used “wisdom of God” as a title for Himself (Luke 11:49). Furthermore, the Messiah indicated that He had greater wisdom than Solomon (Matt 12:42) and a special knowledge of the Father (Matt 11:27). In the Crucifixion, Jesus was the “wisdom of God” (1 Cor 1:24), and to the saints He became “wisdom from God” (1 Cor 1:30).

Whether or not Proverbs 8:22–36 directly describes the divine Word has been debated throughout church history. Those taking the negative position say that because wisdom was “brought forth” (v. 25), it was created—unlike the eternal Son. But this couldn’t have been Solomon’s meaning. If wisdom was created, then at some point God lacked wisdom. Wisdom wasn’t created before everything else, so much as it was an attribute that God always had. That was the king’s point, and the context supports that conclusion. Nevertheless, the figure of wisdom may simply be a literary device. If that is the case, it only seems to describe the Word so well because it is in Him that wisdom finds its substance. As the incarnate Logos, Jesus is God’s wisdom personified.

Other Occasions

Before providing us with a final name for the preincarnate Jesus, Justin wrote “and on another occasion . . .” This suggests that the father was giving us just one more example instead of completing an exhaustive record. The one that was chosen—the Captain who appeared in human form to Joshua—is representative of the other Christophanies that are not specifically identified as either the Word, the Angel, or the glory of Yahweh:

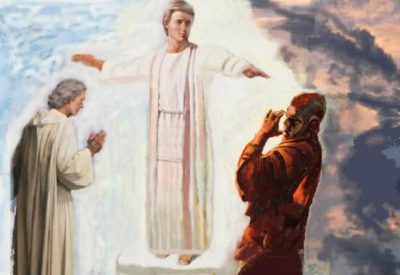

Now it came about when Joshua was by Jericho, that he lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, a man was standing opposite him with his sword drawn in his hand, and Joshua went to him and said to him, “Are you for us or for our adversaries?” He said, “No; rather I indeed come now as captain of the host of the Lord.” And Joshua fell on his face to the earth, and bowed down, and said to him, “What has my lord to say to his servant?” The captain of the Lord’s host said to Joshua, “Remove your sandals from your feet, for the place where you are standing is holy.” And Joshua did so. (Josh 5:13–15)

When God called to Moses from the burning bush He said, “Do not come near here; remove your sandals from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.” (Exod 3:5). The Captain said almost the exact same thing to Moses’ successor. While it was God who spoke from the bush, it was the Angel of Yahweh that appeared in the midst of it. He manifested the Shekinah among the branches and leaves, causing the bush to appear as though it was burning with a fire that did not consume (Exod 3:2–3). The Captain was this same person—both God and the messenger of Yahweh.

We will explore both of these Christophanies in more detail in upcoming articles. For now, consider that Joshua and Jesus share the same name.[9] This helps to underscore that Joshua was a type of Messiah. A type is a sort of prophetic symbol that foreshadows something or someone that was yet to come. Many of the people that were visited by a Christophany acted in some way that corresponded with an aspect of Jesus’ character or actions. In this sense, each of them pointed toward something greater that the Messiah was to accomplish. In the case of Joshua, his actions as a conqueror typified Jesus as the Lion Messiah (e.g., Isa 63:1–6; Zech 14:1–5; Rev 19:11–21). Joshua was the captain of Israel’s army. But Jesus is the true captain; He is the commander of the armies of heaven and Joshua’s superior officer. The type received instruction from the archetype. The inferior copy pointed to the perfect original.

All Those Names

Justin followed his list with an explanation for why each name for the Son was on it:

For He can be called by all those names, since He ministers to the Father’s will, and since He was begotten of the Father by an act of will; just as we see happening among ourselves: for when we give out some word, we beget the word; yet not by abscission, so as to lessen the word [which remains] in us, when we give it out: and just as we see also happening in the case of a fire, which is not lessened when it has kindled [another], but remains the same; and that which has been kindled by it likewise appears to exist by itself, not diminishing that from which it was kindled.[10]

In the ancient world, it was often a son’s role to not only represent his father, but to do so with full authority. When a son was in such a position, he was to be treated as though he was his father. The son’s actions, deeds, and words were considered—often legally—as though his father had performed or spoken them. This is why by calling God His own Father, Jesus was making Himself equal with God (John 5:18). Moreover, when Jesus said that He was one with the Father, the Jews understood that He was making Himself out to be God (John 10:30–33). If a son is the same as his father, then the Son of God is God. And if Jesus was not claiming equality with the Father as deity, then He surely would have corrected the people’s thinking.

In the contexts in which they are often used, the Word, the Angel, the glory, and several other related names are functional synonyms for the Son. Each title designates He who ministers to the Father by explaining Him and accomplishing His will. They all describe a person who is separate from God in heaven, while also being God Himself.

The Son’s fundamental role as the Word speaks to the unique relationship He has with the Father. When we speak, we do not create a new word out of nothing. Rather, it goes forth from us as an extension of something that was already in our minds. Even when a word has left our lips, it isn’t cut off from us—it remains within us as an idea. In like manner, when a fire kindles another fire it begets itself. The new fire doesn’t drain power from the original. It seems to exist as a separate fire in one sense, and yet in another it is the same fire as the original. Think of a large forest fire. We would consider such a blaze to be just a single fire, even though we could identify separate fires within it. A smaller individual fire would serve to explain the overall fire. We could understand it without having to stand in the midst of the larger blaze, only to be incinerated.

No analogy could ever be so perfect as to fully explain God’s nature. Even so, these two help us to understand the role that the eternal Son has within the Godhead and why it is fitting that He should be called by all those names.

The Scriptures Testify

Jesus taught that the Old Testament testifies about Him:

You search the Scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; it is these that testify about Me; (John 5:39)

At the time Jesus said this, the Scriptures referred solely to the Tanakh—the same writings that Christians came to know as the thirty-nine books of the Old Testament. The Old Testament testifies about Jesus in several ways. His coming was foretold in a plethora of messianic prophecies. He was pointed to by countless types and shadows, people and events. And the things the Son has already done were recorded, including those times when He visited man.

The idea of Christophanies can initially come across as astonishing or even unusual. After all, the majority of Christians were brought up to think that Jesus was introduced in the New Testament. But it was Jesus who introduced Genesis. He is the beating heart of the Bible—the hub in the middle of the wheel of Scripture. It isn’t just the New Testament spokes that connect to Him, but every single Word that God has breathed. So, what would actually be unusual—ridiculous even—is if the Son didn’t regularly show up in the first three quarters of the Bible. Jesus has always loved and shepherded His people. The Son served the Father in the New Testament, just as He did in the Old. He was always there.

[1] Trypho was likely a fictional character created by Justin as a literary device.

[2] Roberts et al., Ante-Nicene Fathers Volume I, 227. Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, Chapter LXI.

[3] Singer, ed., The Jewish Encyclopedia, 59.

[4] For a detailed study on why John’s usage of Logos originated in Jewish thought—and not from Greek philosophy or the writings of Philo—see Fruchtenbaum, Yeshua, 208–225.

[5] Intrater, Lunch with Abraham, 32–33.

[6] Fruchtenbaum, Footsteps of the Messiah, 591.

[7] Roberts et al., 227. Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, Chapter LXI.

[8] Ibid., 227–228. Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, Chapter LXI.

[9] Joshua is the English spelling of Jesus’ Hebrew name Yeshua. Jesus is the English spelling of the Greek Iesous.

[10] Ibid., 227. Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho, Chapter LXI.

loved this article! Preaching a series on these at the church I pastor entitled “Jesus in the Old Testament and Why It Matters” Would love to interview the au thor onmy show

I’m happy to learn that it was useful to your sir. This series has been a labor of love. I’m happy to discuss the material: ervin@protonmail.com