Augustine’s influence was so dominant that Amillennialism went largely unchallenged until well into the Reformation. On why Premillennialism did not make an immediate return at that time, John MacArthur explained:

The Reformers had it right on most issues. But they never got around to eschatology. They never got around to applying their formidable skills. You cannot fight the war on every front. And at the great time of the Reformation, they were fighting the war where the battle raged the hottest and that was over the gospel and over the nature of Christ and over salvation by grace through faith and over the authority of Scripture. They were fighting the massive Roman system. And being occupied on those fronts, they never really got to the front of eschatology…[1]

This does not mean that the Reformers held to no eschatological position at all. It means that their high view of God’s word over the traditions of men was not seriously applied to what was a lower priority. This resulted in a lingering Amillennialism.

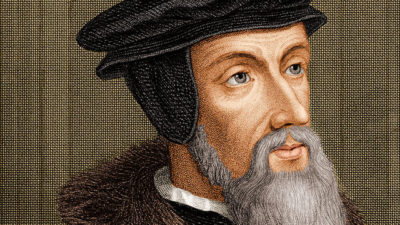

John Calvin’s remarks are emblematic:

But a little later there followed the chiliasts, who limited the reign of Christ to a thousand years. Now their fiction is too childish either to need or to be worth a refutation. And the Apocalypse, from which they undoubtedly drew a pretext for their error, does not support them. For the number ‘one thousand’ [Rev. 20:4] does not apply to the eternal blessedness of the church but only to the various disturbances that awaited the church, while still toiling on earth. On the contrary, all Scripture proclaims that there will be no end to the blessedness of the elect or the punishment of the wicked [Matt. 25:41, 46].[2]

It is rather difficult to find more than a few pages in a row from Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion that lack a reference to Augustine. Such was the level of influence Augustine held over the reformer. Calvin even followed after Augustine in mischaracterizing the beliefs of the chiliasts or early premillennialists. If these fathers really believed that the reign of Christ would come to an end after the Millennium then they deserved to be mocked. Of course this is not what the chiliasts believed, nor is it even a remotely accurate description of Premillennialism in general. The reign of Jesus does not end with the Millennium. He will remain King on the new earth for all eternity. Blessings upon the saints and punishments upon the wicked will last just as long.

And what of Calvin’s brief explanation as to the meaning of the thousand years? The church facing disturbances while toiling on the earth is almost the opposite of reigning alongside King Jesus. Calvin was an exegetical genius on many Biblical subjects. Unfortunately, he did not put the same effort into seriously unpacking the Scriptures when it came to the Millennium. Calvin wrote a commentary on nearly every book of the Bible, but Revelation was not among them. Now frankly it’s too late for John Calvin to fix his work, although he is now a premillennialist in heaven. If only he could just send down one message, that might be it.[3]

JOSEPH MEDE

Joseph Mede (1586-1639) is one of the most fascinating figures from the twilight of the Reformation. He was not only a widely influential church scholar, but also a naturalist and Egyptologist. Mede was well schooled in Biblical languages, subjects he lectured on at Christ’s College of the University of Cambridge. Mede broke with his contemporaries in returning to the literal interpretation of the prophetic Scriptures. His book, The Key of the Revelation, was a clarion call for a return to Premillennialism. Mede was certain that the thousand years of the millennium…represented the future reign of the saints with Christ…Mede Identified the millennium with the future seventh trumpet and the day of judgment, both of which, he argued, would last one thousand years. It was a systematic repudiation of the Reformer’s Augustinianism.[4]

Mede was a harbinger; after him came the flood. William Twisse, Prolocutor of the Westminster Assembly, wrote a preface to the 1643 English translation of The Key of Revelation. In it, he rebuked Augustine for relinquishing the doctrine of Christ’s Kingdom on earth and praised Mede for returning to it.[5] Isaac Newton, arguably the most prolific scientist in history, acknowledged Mede as the greatest influence on his interpretation of Biblical prophecy.[6] The list of Church leaders and Bible scholars following Mede in becoming premillennialists continues at some length.

[1] John MacArthur, “Why Every Calvinist Should Be a Premillennialist, Part 1,” Grace to You, March 25, 2007, accessed April 12, 2016, http://www.gty.org/resources/sermons/90-334/why-every-calvinist-should-be-a-premillennialist-part-1

[2] John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed. John T. McNeill (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1975), 995. Bk. III. Ch. XXV. No. V.

[3] John MacArthur.

[4] Crawford Gribben, The Puritan Millennium: Literature and Theology, 1550-1682 (Revised Edition) (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2008), 43-44.

[5] Ibid., 44.

[6] “Newton’s Life and Work at a Glance,” The Newton Project, accessed August 4, 2016, http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/prism.php?id=15.

Thank you keep up the good work!

Thank you sir.