It is quite common for those who oppose Sola Scriptura (i.e. Scripture alone is the final authority on matters of faith) to posit that it was an invention of the Reformers. This is an easy claim to refute both Biblically and historically. Here the example of Basil of Caesarea is provided.

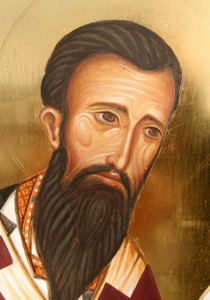

Basil of Caesarea or Basil the Great (ca. 320-379 AD) was a Cappadocian Church Father, contributor to the Nicene Creed and battler of Arianism (the heresy that denied the Trinity and taught that Jesus was a created being). This great theologian and man of faith was also a champion and proponent of Sola Scriptura. In Basil’s letter to Eustathius the physician it is written:

They are charging me with innovation, and base their charge on my confession of three hypostases, and blame me for asserting one Goodness, one Power, one Godhead. In this they are not wide of the truth, for I do so assert. Their complaint is that their custom does not accept this, and that Scripture does not agree. What is my reply? I do not consider it fair that the custom which obtains among them should be regarded as a law and rule of orthodoxy. If custom is to be taken in proof of what is right, then it is certainly competent for me to put forward on my side the custom which obtains here. If they reject this, we are clearly not bound to follow them. Therefore let God-inspired Scripture decide between us; and on whichever side be found doctrines in harmony with the Word of God, in favor of that side will be cast the vote of truth.[1]

The Arians did not just deny the Trinity because they felt that Scripture did not teach it, but also because their own traditions or custom did not. Basil responded to this claim by saying that he could put forth his own custom which asserted the Trinity. At that point each side would reject the opposing custom. Therefore, neither side’s custom could not be a source of authority. For customs often contradict one another. This is even the case within the same church as opinion changes custom over time. Basil’s solution was not to claim that his custom was one that had superior authority. Instead, he looked to Scripture to decide between the customs. Only those doctrines found to be in harmony with God’s Word would be considered worthy.

Elsewhere in Basil’s treatise on morality he writes,

What is the mark of a faithful soul? To be in these dispositions of full acceptance on the authority of the words of Scripture, not venturing to reject anything nor making additions. For, if “all that is not of faith is sin” as the Apostle says, and “faith cometh by hearing and hearing by the Word of God,” everything outside Holy Scripture, not being of faith, is sin.[2]

A soul that was truly faithful to the God described in Scripture was one who put full acceptance on the authority of Scripture. Once one rejected anything taught in Scripture or added doctrines to it, then the beliefs that resulted would be outside of faith and therefore a sin. Does that mean that the traditions of the church fathers are completely useless? No.

We are not content simply because this is the tradition of the Fathers. What is important is that the Fathers followed the meaning of the Scripture.[3]

Basil was happy to believe in the traditions of those Church fathers before him. However, he could not be satisfied in relying on those alone. What mattered is whether or not those who produced the traditions adhered to the meaning of Scripture. The traditions of the Church were not superior to Scripture or even on an equal level. Rather, the only authority the traditions or customs had was in where they followed what Scripture had already declared.

The Scriptures were inspired by God. And they alone are enough to make the man of God complete and equipped for every good work (2 Tim. 3:16-17). Obviously Basil understood this as he looked to what was written by God for his final authority over the traditions of mere men.

[1] Basil the Great, The Letters, Letter 189 (To Eustathius the Physician).

[2] Basil the Great, The Morals, 72:1.

[3] Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit, ch. 7.

Sometimes Protestant apologists try to bolster their case for

by using highly selective quotes from Church

Fathers such as Athanasius, John Chrysostom, Cyril of Jerusalem,

Augustine, and Basil of Caesarea. These quotes, isolated from the

rest of what the Father in question wrote about church authority,

Tradition and Scripture, can give the appearance that these

Fathers were hard-core Evangelicals who promoted an unvarnished

principle that would have done John Calvin proud.

But this is merely a chimera. In order for the selective “pro-

” quotes from the Fathers to be of value to a

Protestant apologist, his audience must have little or no

firsthand knowledge of what these Fathers wrote. By considering

the patristic evidence on the subject of scriptural authority in

context, a very different picture emerges. A few examples will

suffice to demonstrate what I mean.

Basil of Caesarea provides Evangelical polemicists with what they

think is a “smoking gun” quote upholding :

“Therefore, let God inspired Scripture decide between us; and on

whichever side be found doctrines in harmony with the Word of God,

in favor of that side will be cast the vote of truth” (). This, they think, means that Basil would have been

comfortable with the Calvinist notion that “All things in

Scripture are not alike plain in themselves, nor alike clear unto

all; yet those things which are necessary to be known, believed,

and observed, for salvation, are so clearly propounded and opened

in some place of Scripture or other, that not only the learned,

but the unlearned, in a due use of the ordinary means, may attain

unto a sufficient understanding of them” (

Yet if Basil’s quote is to be of any use to the Protestant

apologist, the rest of Basil’s writings must be shown to be

consistent and compatible with . But watch what

happens to Basil’s alleged position when we look

at other statements of his:

“Of the beliefs and practices whether generally accepted or

enjoined which are preserved in the Church, some we possess

derived from written teaching; others we have delivered to us in a

mystery by the apostles by the tradition of the apostles; and both

of these in relation to true religion have the same force” (, 27).

“In answer to the objection that the doxology in the form with the

Spirit’ has no written authority, we maintain that if there is not

another instance of that which is unwritten, then this must not be

received [as authoritative]. But if the great number of our

mysteries are admitted into our constitution without [the] written

authority [of Scripture], then, in company with many others, let

us receive this one. For I hold it apostolic to abide by the

unwritten traditions. ‘I praise you,’ it is said [by Paul in l

Cor. 11:1] that you remember me in all things and keep the

traditions just as I handed them on to you,’ and Hold fast to the

traditions that you were taught whether by an oral statement or by

a letter of ours’ [2 Thess. 2:15]. One of these traditions is the

practice which is now before us [under consideration], which they

who ordained from the beginning, rooted firmly in the churches,

delivering it to their successors, and its use through long custom

advances pace by pace with time” (, 71).

Such talk hardly fits with the principle that Scripture is

formally sufficient for all matters of Christian doctrine. This

type of appeal to a body of unwritten apostolic Tradition within

the Church as being authoritative is frequent in Basil’s writings.

Although you pasted these comments from another site I will still interact a bit. In regards to your first paragraph: This is a broad claim that means nothing until each quote and the context of it is considered. Furthermore, could I not easily make the same charge against Roman Catholics? The RCC’s abuse of history is nothing short of astonishing. For example, several individuals are said to have been popes in the ante-Nicene period and yet there is no evidence that this is the case whatsoever, or that such an office even existed.

Note that Basil’s teachings on the authority of Scripture are not concluding that traditions have no authority. Sola Scriptura means that Scripture alone is the final and strongest authority, not that Scripture is all alone in every respect. Basil’s words I provided speak for themselves and in no way contradict the passages you provided. Also you should be careful in inferring that the traditions early fathers spoke about are one in the same as what the Roman Catholic Church teaches.

I agree with Matthew here, and am looking forward to learning more from this blog. That oral, unwritten tradition exists is one thing. To insist that it is on par with the Holy Scriptures and that only together do they constitute the fullness of divine revelation, as the Church of Rome does in Dei Verbum 9, is quite another matter. It is also untenable for the plain fact that the Holy Scriptures have been uniquely preserved, attested to, and well defined. They are sure as nothing else is, categorically without equal. Tradition, especially oral or unwritten, is comparatively nebulous. It is less defined, less attested to, and therefore simply less reliable.

Thanks so much for the articles. I found you site by researching Christophanies.

My joy; thank you.