This article is part of a series on Old Testament Christophanies. For important background information, see An Introduction to Old Testament Christophanies–with Justin Martyr.

The binding of Isaac, known to the Jews as the Akedah (Hebrew for binding), is the premiere example of the Lord testing a man’s faith and his love of God. Abraham demonstrated and proved his faith through action and obedience by offering up his son on the altar (Jas 2:21–23). Now let’s be honest, this can be a difficult and heartbreaking story to come to terms with. To some, the test makes God seem cruel and arbitrary. But there is much more to Genesis 22 than what there appears to be on the surface. The chapter records a prophetic play—one meant to connect the patriarch of the faithful and his son to the death and resurrection of God’s only Son. And it is the Son of God, as the Angel of the Lord, who stops Abraham from sacrificing his son Isaac.

The binding of Isaac, known to the Jews as the Akedah (Hebrew for binding), is the premiere example of the Lord testing a man’s faith and his love of God. Abraham demonstrated and proved his faith through action and obedience by offering up his son on the altar (Jas 2:21–23). Now let’s be honest, this can be a difficult and heartbreaking story to come to terms with. To some, the test makes God seem cruel and arbitrary. But there is much more to Genesis 22 than what there appears to be on the surface. The chapter records a prophetic play—one meant to connect the patriarch of the faithful and his son to the death and resurrection of God’s only Son. And it is the Son of God, as the Angel of the Lord, who stops Abraham from sacrificing his son Isaac.

God tested Abraham’s faith by telling him to take his only son, whom he deeply loved, and to sacrifice him on one of the mountains of Moriah (vv. 1–2). The point of the test was not to see if Abraham would do one of the worst things imaginable just because he was told to. Rather, it was to see if the patriarch was willing to do what God would actually do: offer up his only son. The land of Moriah was a mountainous region extending around Jerusalem, located approximately forty-five miles north of Beersheba—where Abraham was traveling from. It is atop these mountains where the Angel of the Lord appeared to David who then built an altar to the Lord (2 Sam 24:16–25). It is on this same site where Solomon built the First Temple (2 Chr 3:1), where the Second Temple was constructed, and where the Temple Mount of today remains. Other famous mountains of Moriah include Zion and the Mount of Olives. And most significantly, one of these mountains is Golgotha—where Jesus was crucified. According to rabbinical tradition, Isaac was thirty-seven at the time of Abraham’s testing.[1] Even if he wasn’t quite that old, he was no longer a child given the physicality needed to travel great distances and to carry a good deal of wood up a mountain. Isaac may have well been the age Jesus was at the time of the crucifixion.

Abraham rose early the next morning, saddled his donkey, chopped some wood for the offering, and then departed with his two servants and Isaac. On the third day, Abraham raised his eyes and he could see the place from afar (vv. 3–4). He didn’t just see the place with his natural eye, but with the eye of a prophet. Remember, Jesus said that Abraham saw His day and was glad (John 8:56). On some level Abraham knew that his coming test went beyond himself and Isaac, that it reached into the future—to the death and resurrection of Messiah Jesus. Abraham saw the place on the third day: a day for revelation. On the third day, Joseph told his brothers what they needed to do to live (Gen 42:18). It was on the third day when God revealed Himself to the Israelites at Sinai (Exod 19:16). By faith Rahab told the spies to hide in the hill country for three days (Josh 2:16). On the third day of her fast, Esther put on royal robes that so attracted the attention of the king that she was able to save the Jewish people (Esth 5:1–3). After two days of judgment, the Lord will revive and raise up a repentant Israel (Hos 6:1–2). Jonah was in the belly of the fish for three days and three nights (Jonah 1:17; Matt 12:40). And the greatest reveal of all happened on the third day, when the Lord Jesus Christ was resurrected (e.g., Matt 16:21).

As they neared the place of the offering, Abraham and Isaac left the donkey and the servants behind (v. 5). In Midrash Rabbah Genesis, a key Jewish commentary written around 300–500 AD, it is said that the inclusion of the donkey prefigured the coming of the Messiah to Jerusalem.[2] The rabbis based this on Zechariah 9:9, where the messianic king is prophesied to come to Jerusalem humbly mounted on a donkey. The donkey is a servant animal, and so represents the Messiah as a servant when He is seated upon one. We believe that Zechariah’s prophecy came to pass at the triumphal entry of Christ (Matt 21:1–11). While there is disagreement as to His identity, ancient Jewish rabbis and modern Christians alike have seen the foreshadowing of the Messiah in Genesis 22.

Notably, Abraham told the servants that both he and Isaac would return after worshipping God (v. 5). Abraham had faith that, one way or another, God would keep His promise to bring about countless descendants through Isaac. Either God would preserve Isaac from being sacrificed or resurrect him from the dead afterward. The writer of Hebrews implied as much in 11:17–19:

By faith Abraham, when he was tested, offered up Isaac, and he who had received the promises was offering up his only begotten son; it was he to whom it was said, “In Isaac your descendants shall be called.” He considered that God is able to raise people even from the dead, from which he also received him back as a type.

A literal translation of the final phrase has Abraham receiving Isaac back as a parable (Gr. parabole) (cf. Hos 12:10). Unlike most parables, which are fictional, this one was a historical event meant to illustrate the future death and resurrection of God’s only begotten Son.

Abraham held the fire and the knife, but placed the wood for the offering upon Isaac for him to carry (v. 6). The same midrash compared Isaac to “one who carries his stake on his shoulder”[3] (referring to an execution victim being forced to bear his own stake or cross). Isaac carried the piece of wood on which he was to be executed—much like how Jesus carried His own cross to His crucifixion. Seeing both the fire and the wood, Isaac asked his father where the lamb was for the offering. Abraham answered, “God will provide for Himself the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.” (vv. 7–8). On the surface it would seem that this was Abraham’s way of subtly informing Isaac that he was the sacrifice. But on a deeper level, the level of faith, Abraham prophesied the coming of the Messiah, the Lamb of God. Before Isaac got his answer it is written that “the two of them walked on together” (v. 6), meaning that he and his father were in agreement (cf. Amos 3:3). Even after Isaac found out that he was facing death it remained the case that “the two of them walked together” (v. 8). At his father’s request, Isaac went willingly to his death for the glory of God.

The Lamb of God

When they arrived at the place God had led them, Abraham built an altar and arranged the wood on it. He bound Isaac, laid him upon the wood, and took hold of his knife (vv. 9–10). Just as Abraham was about to drive it into his son, the Lord intervened:

But the angel of the Lord called to him from heaven and said, “Abraham, Abraham!” And he said, “Here I am.” He said, “Do not stretch out your hand against the lad, and do nothing to him; for now I know that you fear God, since you have not withheld your son, your only son, from Me.” (Gen 22:11–12)

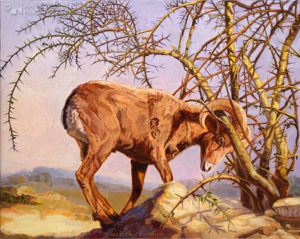

The Angel went from speaking about God in the third person to speaking as God in the first person. The Angel of the Lord is the Son of God, who speaks on behalf of God while also being God. Just as the Angel finished speaking, Abraham beheld a nearby ram with its head caught in a thicket. So Abraham took the ram and sacrificed it instead of his son (v. 13). The Lord may have directed the ram there or He may have created it just for this occasion. A different animal was given to make it clear that this wasn’t the lamb that God was supposed to provide. The Hebrew for word ram (‘ayil) is rooted in the concept of strength, and is so used to symbolize men of great renown (Dan 8:3, 20). The ram, with its head stuck in the branches and briers of the thicket, was a powerful picture of the mighty Davidic King wearing a crown of thorns.

The Angel went from speaking about God in the third person to speaking as God in the first person. The Angel of the Lord is the Son of God, who speaks on behalf of God while also being God. Just as the Angel finished speaking, Abraham beheld a nearby ram with its head caught in a thicket. So Abraham took the ram and sacrificed it instead of his son (v. 13). The Lord may have directed the ram there or He may have created it just for this occasion. A different animal was given to make it clear that this wasn’t the lamb that God was supposed to provide. The Hebrew for word ram (‘ayil) is rooted in the concept of strength, and is so used to symbolize men of great renown (Dan 8:3, 20). The ram, with its head stuck in the branches and briers of the thicket, was a powerful picture of the mighty Davidic King wearing a crown of thorns.

Abraham named the top of the mountain Yahweh-Yireh, meaning the Lord will provide. Hundreds of years later, the name was still used as a proverb: “In the mount of the Lord it will be provided” (v. 14). The expectation was that one day God would provide the lamb that Abraham prophesied. This is why when John the Immerser saw Jesus walking toward him, he proclaimed, “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29). Jesus is the true Lamb of God—Isaac and the ram were types which foreshadowed the sacrifice that only He could make. So when the Son of God stopped Isaac’s sacrifice, it was as if He was saying, “This isn’t your role; it’s mine.” The traditional view is that the binding of Isaac happened on what became the Temple Mount. But there are many mountains in the Moriah region. The one mentioned in 2 Chronicles 3:1 isn’t necessarily the same as Yahweh-Yireh. If the Lord was to provide on the same place where Isaac was bound, then Yahweh-Yireh can only be Golgotha: where the Lord provided the Lamb of God. The Temple Mount set near Golgotha in Jerusalem is a physical depiction of the shadowy and imperfect sacrificial system of the Mosaic Covenant pointing to the perfect sacrifice of the New Covenant.

The Angel had a final message for Abraham:

Then the angel of the Lord called to Abraham a second time from heaven, and said, “By Myself I have sworn, declares the Lord, because you have done this thing and have not withheld your son, your only son, indeed I will greatly bless you, and I will greatly multiply your seed as the stars of the heavens and as the sand which is on the seashore; and your seed shall possess the gate of their enemies. In your seed all the nations of the earth shall be blessed, because you have obeyed My voice.” (Gen 22:15–18)

Abraham’s obedience vindicated his faith, and in response the Angel confirmed the covenant with an oath. He made an eternal promise to Abraham, swearing by His own name since He could swear by none higher (Heb 6:13). The Angel is the same divine person who had made these promises and ratified the covenant many years earlier. His visitations and communications with Abraham and his family over the years were leading up to this moment. The Son of God had a personal relationship with Abraham, transforming the patriarch into the man he was supposed to become.

After the Angel finished speaking, Abraham returned to his servants and they traveled back to Beersheba (v. 19). Verse 19 doesn’t specifically mention Isaac leaving with his father. This lent to a Jewish tradition being developed that Isaac was actually sacrificed. For example, Midrash HaGadol explains that Isaac died and went to Gan Eden (the afterlife paradise) for three years before returning to marry Rebekah.[4] While this speculation goes too far, there is some truth to Isaac “dying” and “resurrecting.” After all, Abraham received Isaac back as a type of the risen Christ (Heb 11:19). The unbinding of Isaac foreshadowed the resurrected Jesus leaving behind His burial shroud.

The offering of Isaac was central to much of Jewish thought and theology on atonement and resurrection. Geza Vermes, the eminent 20th century Bible scholar of Jewish descent, explained that

According to ancient Jewish theology, the atoning efficacy of the Tamid offering [the daily burnt offering], of all the sacrifices in which a lamb was immolated, and perhaps, basically, of all expiatory sacrifice irrespective of the nature of the victim, depended upon the virtue of the Akedah, the self-offering of that Lamb whom God had recognized as the perfect victim of the perfect burnt offering.[5]

There is a sense in which the death of Isaac, as a righteous man, could pay for the sins of subsequent generations. The offerings of the sacrificial system were only effective because they were based upon the “death” of Isaac. The reasoning of the ancient Jews is sound, except for one small problem: Isaac wasn’t a perfect sacrifice. To be sure, he was a relatively innocent and righteous man when compared to most others, but not when compared to a thrice holy God. These Jewish thinkers were on the right track; they just needed to go one step further and view the Akedah itself as based upon an even greater sacrifice: the offering of the only begotten Son of God—a lamb, unblemished and spotless.

Vermes also found that

Isaac was granted a new life by God. For the midrashists, therefore, he was the prototype of risen man, and his sacrifice followed by resurrection was, in some way, the cause of the final Resurrection of mankind. In short, the Binding of Isaac was thought to have played a unique role in the whole economy of the salvation of Israel, and to have a permanent redemptive effect on behalf of its people. The merits of his sacrifice were experienced by the Chosen people in the past, invoked in the present, and hoped for at the end of time.[6]

The idea that the resurrection of a perfect man could somehow empower the resurrection of mankind is absolutely correct. Though again, Isaac wasn’t perfect. The risen Christ is the firstfruits of those who have died (1 Cor 15:20). As the firstfruits were emblematic of the entire harvest (Lev 23:10–11), so it is with Jesus. He was the first to be resurrected by His own power. All resurrections, before and after, were only made possible by the risen Christ.

As the Lamb, Jesus was delivered over to the cross by the predetermined plan and foreknowledge of God (Acts 2:23). All of those who are in Christ have their names written from the foundation of the world in, “the book of life of the Lamb who has been slain.” (Rev 13:8). The death and resurrection of Messiah Jesus is the centerpiece of God’s eternal plan to redeem a people for Himself. As a fellow human being, Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son can help us begin to understand the love that God the Father had for us when He gave His only begotten son. Abraham passed his test of faith. As a result, the obedience of two men illustrated the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ nearly two thousand years before the incarnation. Their act of faith took place in the shadow of the Lamb. But oh how light that shadow is, and how brightly the Gospel shines forth!

[1] This is the oldest Isaac could have been. He was born to Sarah when she was ninety (Gen 17:17), while she died at age 127 sometime after Abraham and Isaac departed the land of Moriah (Gen 23:1–2).

[2] Midrash Rabbah on Genesis 22:5

[3] Midrash Rabbah on Genesis 22:6

[4] Midrash HaGadol on Genesis 22:19

[5] Vermes, Scripture and Tradition, 211.

[6] Ibid., 207–208.

Great explanation

Thank you.

This is a very detailed explanation.

Thank you